My research suggests that pirate radio can be divided into 3 distinct 'eras'

1960s:

- Pirate radio stations are set up to meet music demands not being met by BBC radio

- Broadcasting from ships and offshore rigs as a loophole around broadcasting laws

- Mostly played rock n roll and pop music to cater to the demand not being met by BBC

- Audience mostly young people

- Eventually BBC restructured in retaliation, splitting into several radio stations with a broader broadcasting programme

70s-2000s:

- Most pirate stations move on land, broadcasting from inner city tower blocks

- Radio stations become more community based, focusing on specific cities and catering for Britain's black and Asian communities

- Many now popular British music genres have their roots in pirate radio - drum n bass, grime, acid house, jungle, garage

- Many pirate stations are connected closely with the UKs illegal rave scene

Current:

- Although some pirate radio stations are still running, many of the old ones became licensed and commercialised

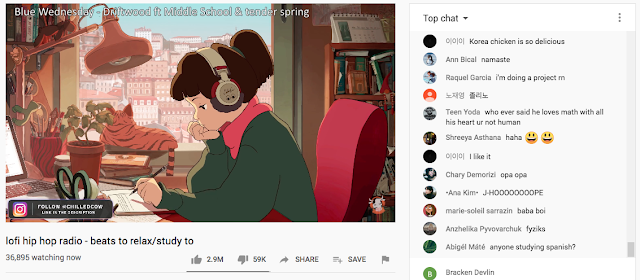

- Most young people don't listen to radio now - DIY broadcasting has moved to 'streaming'

- Thanks to the internet, streaming can be done for free by anyone with access to facebook, instagram, youtube, twitch

- Podcasting is also a modern form of DIY broadcasting, in which people upload audio of them discussing a wide range of topics online -

I am going to focus my project on the current era of pirate radio - I feel that, due to advances in technology, there is a lot of untapped potential in DIY broadcasting.

My project aims:

- Introducing the feeling of underground community which pirate radio embodies to a new generation

- Giving musicians and thinkers who are unable to get mainstream radio play space to share their work

- Alleviating loneliness in a generation which, partly due to Covid19, is spending a lot of time isolated for others

Streaming - what is it?

a method of transmitting or receiving data (especially video and audio material) over a computer network as a steady, continuous flow, allowing playback to start while the rest of the data is still being received. (i.e the media can be played without the whole file needing to be downloaded)

live streaming means the content is being broadcast in real time

My website will be live streaming content, much like a traditional radio - users cannot listen to past content and must tune in at specific times to listen to the shows/ DJ sets. I am making this decision because:

1. It pays homage to the roots of the project

2. Consumers are overwhelmed with choice now - almost every episode of everything ever is available online. Having something stream only once makes it special.

So, I have the purpose of the website decided. Now it is important to consider how it will be presented.

- how can the experience be made immersive?

- how can the user be made excited/ intrigued/ want to come back to the site?

- there are many places to livestream music - why is this site special?

Key words:

-Immersive

-Clandestine

-Community

-DIY

-Subculture

Ideas/ references:

Something to visually represent how many users are online/ on each page/ users can mark their presence

- There is an online game server where every users mouse shows at once and can be seen moving around the screen. We can't remember the name of the site but heres a mockup. The users instinctually make their mouse cursors interact with each other.

How Live Streaming Boosted Community During Lockdown

As the Government reopens our high streets and continues to relax social distancing measures, we’re reflecting on the ways we kept entertained, connected, and sane during lockdown, and ask if live streams really were our saviour?

Since the lockdown was announced, live-streaming views have increased by 45% across multiple platforms such as Twitch, Facebook, and of course Youtube. The average screen time per person has increased by 76% and even audio streaming has grown by 7.1%. Sites like Netflix have seen over 16 million new sign-ups and there has even been a 31% rise of Spotify subscribers.

The early adopters and big winners

One of the obvious live streaming big winners of the last 12 weeks has to be Joe Wicks, his morning 9am #PEwithJoe sessions on YouTube have seen him achieve over 700 million views and raise an amazing £500K to donate to NHS Charities. With all gyms and leisure centres remaining closed, fitness influencers, in general, continue to be big winners in the live streaming space, as individuals stay committed to working out at home.

The popularity of at-home workouts has been such that the future of the traditional gym workout will likely have changed forever for many.

Another group quick to maximise live streaming to stay in touch with their communities were food influencers. Sales in the restaurant industry dropped by 20% between January and March after all were forced to close their doors. A handful were able to operate a delivery service with a limited menu and a small team but with the industry’s sales dropping substantially, many culinary talents are turning to Instagram live to teach the nation how to cook restaurant-quality food.

Massimo Bottura is a chef and patron for popular Italian restaurant, Osteria Francescana. Since the lockdown was announced, Massimo has taken to Instagram live nearly every day at 3pm to teach his followers how to make delicious, homemade Italian meals through his series ‘KitchenQuarantine’. Each episode gains anywhere between 100-500K views, and his follower count has seen the benefit too.

At the beginning of 2020 Massimo had around 1 million people following his Instagram account since he launched his KitchenQuarantine series, he has seen half a million more accounts join his community in a matter of weeks.

Brands were quick to catch on to the success that influencers were having with their live streams too. Bobbi Brown started to list a daily schedule of self-care live streams featuring their talented make-up artists.

Their ‘Relaxing Skincare’ live stream secured its place as the “highest performing IG Live to date” with over 17,000 views. But why was it so popular? Before launching this initiative, the brand had its followers complete a survey to find out what it was that their fanbase wanted to see whilst stuck at home. By communicating with their followers and delivering as promised, their community has only gotten bigger and more dedicated.

Platforms that facilitated the trend

Streaming platform giant Youtube amassed 300 billion views in the first quarter of 2020, a 13% increase compared to the end of 2019. Additionally, the audience usage of the platform has surged by 15.3%. With 39 billion more people to entertain, the pressure was on for streamers to continue to deliver high-quality, positive content.

On the 30 April through the ‘Youtube Originals’ channel, the site launched a four-hour live stream titled, ‘Stream #With Me’, a live-stream cast with some of the platform’s most popular stars. Viewers were encouraged to donate to the NHS ‘Charities Together’ campaign throughout the livestream.

Donations have obviously been essential throughout the pandemic, in response Instagram has made it’s donation stickers available for inclusion in live streams hosted by content creators. The Instagram donation stickers were first made available for UK charities in July of last year, but this recent change allows followers to donate in real-time while watching live streams from their favourite influencer.

During Stream #WithMe, the creators shared their own lockdown stories, as well as tips on how to keep entertained, active and positive throughout the pandemic, whilst still creating a positive atmosphere for the audience to escape to for four hours of the day. While these creators had the guidance of a billion-dollar company behind them, this is something that should definitely be commended.

Are live-streamed events the future?

June is here. It is the month of Pride and a month that is usually celebrated globally with parades, street parties and speaking events. And most importantly, used to raise awareness for current political issues facing the LGBTQ+ community.

Since March, organisers around the world have been cancelling their Pride events in the wake of COVID-19. Sadly over 500 events worldwide have been cancelled so far.

However, Pride month is not a force to be reckoned with. The LGBTQ+ community needs a platform, and many media brands and LGBTQ+ brand allies are stepping up to the plate and giving these people the voice they need.

Condé Nast’s LGBTQ+ platform, Them, has moved their Pride events online, by launching their ‘Out Now Live’ programme. A live stream celebration that is not only raising money for the Ali Forney Center but will feature Elton John, Cara Delevingne, Whoopi Goldberg and an array of stars from the LGBTQ+ community. The month is filled with performances, speeches, and stories from their lives, all live-streamed via Condé Nast’s Instagram platform.

The class of 2020 are also feeling a whole lot of disappointment this year. What was supposed to be the best year of their lives turned into the very harsh reality of exhibitions, showcases, and graduate events all cancelled, and students studying the arts have to bear most of the brunt.

TikTok has partnered with the Graduate Fashion Foundation who are moving their Graduate Fashion Week onto the app. The platform is giving final year fashion students a chance to showcase their work via live streams on the app and is even giving them the chance to design fashionable, ethical merchandise for TikTok.

The transition of the bi-annual London Fashion Week from the catwalk to online could have been a devastating announcement for the fashion and beauty industries. But the British Fashion Council has taken the event onto the LFW website and has a full schedule of live stream discussions, digital showrooms and runways that are all open to the public.

The chief executive of the British Fashion Council said: “by creating a cultural fashion week platform, we are adapting digital innovation to best fit our needs today and enacting something to build on as a global showcase for the future. The other side of this crisis, we hope, will be about sustainability, creativity and product that you value, respect and cherish”.

Even Premier League football is going virtual. CEO Richard Masters is looking for ways to improve the live experience for football fans whilst games have to be played behind closed doors, such as sound effects of supporters in the stadium or the use of large screens streaming the reactions of fans.

Creating innovative opportunities

The Coronavirus outbreak halted almost all traditional forms of production, events and human interaction, forcing everyone to explore new ways to stay connected and entertained.

In what was being called, “the new normal”, the public desperately looked for ways to connect with the outside world whilst wanting to stay safe. Of course, social media was their saving grace and streaming in particular provided a sense of shared experience and community.

It also opened up a range of innovative opportunities for brands, platforms and event hosts and, in doing so, will likely have changed the future for many as they realise the possibilities and power of streaming.

https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/coronavirus-lockdown-stream-concerts-online-b480824.html

Why live-streamed gigs and moshing from home should stay

Stream team: how Boiler Room changed the face of live music

They went from a webcam DJ session in east London to a global streaming sensation. And now any music, however niche, can find a crowd. But where does this upstart company go next?

It’s 9pm, Thursday night. The queue snakes from the door of the north London club Electrowerkz, down the street and out on to the main road. There are around 800 twentysomethings waiting to get in, shuffling feet and thumbing smartphones. It’s an impressive crowd for a weeknight, but the horde here is only a fraction of the audience for tonight’s show.

This is the fifth birthday party for Boiler Room, internet-based documenter of club culture and self-proclaimed online home of the underground. As the DJs inside play records covering the spectrum of dance music, their every motion will be videoed and broadcast live on YouTube to hundreds of thousands of people around the world as they eat their dinners or sit at their office desks. It’s an event spanning three continents: four similar anniversary parties are being broadcast from Berlin, Tokyo, Los Angeles and New York.

While Boiler Room can’t definitively claim to have invented the format of live-streaming music, the last half-decade has seen it comprehensively dominate. It cites stats that can make you dizzy, claiming to have streamed over 3.5bn minutes of music since starting out, with audiences of up to 400,000 tuning in to watch any of up to 100 live sets (and a record 10.6m watching Carl Cox in Ibiza on YouTube). From its early days of broadcasting DJs, it’s ballooned into a media upstart clambering rapidly to the top, buoyed by idealism and naked ambition. Not everyone in the industry likes it but no one can ignore it.

Inside the club, Boiler Room founder Blaise Bellville is jittery, fidgeting his lofty frame (he’s a cloud-bursting 6ft 7in). “I hate this part of the night,” he says, as he rushes back and forth, trying to find a missing guestlist. All Received Pronunciation and wheeler-dealer hustle, like a public school Arthur Daley, Bellville has a background that reads like a Dickens plot: born with aristocratic links, his family went bankrupt when he was four years old. “It’s not a rags-to-riches story by any means,” he insists. “I was very fortunate. I got all the confidence that privileged education brings. But I didn’t have any money.”

It’s quite possible that proximity to wealth, without having too much of it, explains Bellville’s restless search for the next big scheme. Back in 2010, he was splitting his time between running a magazine-style website called Platform and persuading an investor to convert a derelict east London warehouse into artists’ studios. “One night I was wandering around the building and found this old boiler room, it was fucking cool,” he says. “I moved my turntables in there, bought a shitty little CDJ [CD turntable], and the plan was to record mixes each week. I realised we could record on a cheap camera and broadcast it live. It was like a teenage hangout in a bedroom.” They pulled the sign off the wall to use as a logo, and Boiler Room was born.

These shows were repeated weekly, with various local DJs dropping in to play sets that were as much about showing off the records they loved as they were about making people dance. Its format – shaky web camera fixed in front of the DJ decks, a small invite-only group of clubbers milling around behind them – soon became a trademark, and an audience uncatered for by mainstream radio or TV began to tune in every week. It wasn’t just a chance to hear fresh dance music without setting foot in a club, it was also a chance to hear music that would rarely get played in a club at all.

“Around 2010, the underground had disappeared,” says Bellville. “The charts were full of terrible music. People gathered around the show, they could talk in the forums and find a voice.” As a result, the Boiler Room forum became notorious, a place where the crowd featured on the feed – studiously bored hipsters mooching like recalcitrant teenagers at an adults’ party – were mercilessly mocked. This crowd was as far as you could get from the nutty ravers of 90s dance TV shows such as Dance Energy, but they provided the aesthetic that helped Boiler Room to spread.

By the start of 2011, the live shows were pulling in viewers in the tens of thousands. Rolling Stone put Bellville in its list of the 50 Most Important People In EDM. At this point, the small team sensed an opportunity to go global. But their first attempt at putting on a superstar DJ, Diplo, was a disaster. “Diplo played the most awful set ever,” says Bellville. “He totally misjudged it, it was like bad dubstep. He’s a great DJ, but he thought he was in Vegas. But things like that provoked the reaction online that helped us find our voice. It allowed people to rally together and be like: ‘We all think this is shit.’ It was a turning point because we’d been wondering how to get bigger, and we realised that going more commercial wasn’t the way. Our fan base liked underground music and so did we.”

It was then that they started to refocus on localised scenes. They booked easyJet flights to Berlin in order to showcase a trainspotter’s dream of little-known techno DJs. The debut Berlin session was spiky, non-commercial fare, and the shows were instantly popular. Boiler Room had unlocked the web’s potential for collectivism. On a local level, the DJs playing on the Berlin show might just about have the fans to fill a decent-sized nightclub; on a global level, they had enough to fill stadiums. They repeated the trick further and further afield, filming DJs spinning abstract hip-hop in Los Angeles, or favela funk from São Paulo. Whole swaths of previously inaccessible music were being made easily available, and DJs started seeing playing on Boiler Room as a way of tripling their fan base in the space of an hour-long set.

Inevitably, there were criticisms: how can a culture centred around dancing be reduced to watching a DJ on a screen? Other than the occasional wild card (memorably, German techno producer Anklepants performed in clown pantaloons and a rotating prosthetic cock nose), watching most DJs command the decks isn’t thrilling viewing. But in spite of that, Raj Chaudhuri, Boiler Room’s head of music, says its audience digests content in a number of ways. “The way that people consume Boiler Room varies massively,” he says. “In Russia, there are places where bar owners are running the stream through a big soundsystem and charging for people to come in and dance. The beautiful thing about Boiler Room is that you have a choice in how engaged you want to be.”

In this context, Boiler Room becomes less of a TV broadcast and more like a vast and carefully curated Spotify playlist. Still, there’s one crucial difference: this playlist is created live, with no indication of what might come. The unpredictable trappings of live performance, the possibility that at any moment you might hear something sublime or disastrous, is uniquely enticing.

These days, however, Boiler Room is branching out. It covers a nebulous range of genres – as likely to film Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood conducting the London Contemporary Orchestra as it is to record Ghostface Killah spitting bars from a New York back room – and, far from the previously static setup, it’s now from multiple camera angles. In doing so, it’s actually moving closer to traditional music television, and the talk is of the next Boiler Room extension being into making music documentaries. It seems like its greatest innovation was realised early on; when you’re broadcasting to the world, everything, no matter how niche, can find an audience, in some cases far bigger than anyone would have expected.

After the anniversary party, Gabriel Szatan, Boiler Room’s music editor, emails me to describe it, with a certain wry self-awareness: “Within the music world, Boiler Room is Uber,” he writes. “Rapid expansion, considerable disruption, and no small amount of backlash generated.” Perhaps realising that brand jargon misses the crucial point of the channel, he finishes with a caveat: “Oh, plus it’s fun. It’s absurdly fun.”

on How Live Streaming Boosted Community During Lockdown